Please use this shareable version responsibly. Consider sharing in a digital format before printing onto paper.

- Process and meetings

- Transparency and Reporting

- Reporting and review

- Reporting and review under the Convention

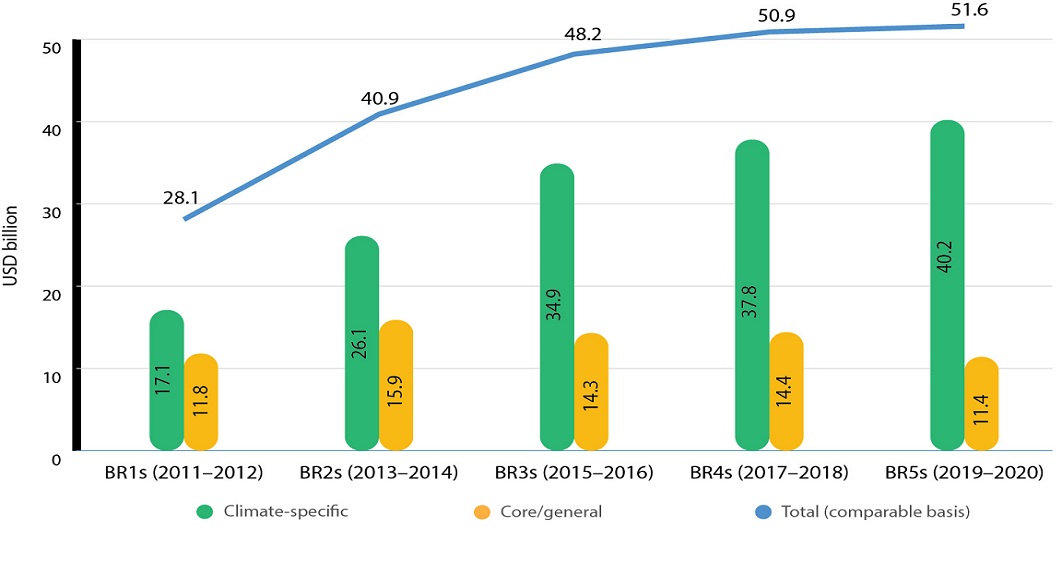

- National Communications and Biennial Reports - Annex I Parties

- Compilation and Synthesis Reports

About transparency

Reporting and review

Overview

Reporting and review under the Paris Agreement

Reporting and review under the Convention

National Communications and Biennial Update Reports - non-Annex I Parties

National Communications and Biennial Reports - Annex I Parties

National Communication submissions

Eighth National Communications - Annex I

Seventh National Communications - Annex I

Sixth National Communications - Annex I

Fifth National Communications - Annex I

Fourth National Communications and Reports Demonstrating Progress under the Kyoto Protocol - Annex I

First, Second, Third National Communications - Annex I

Biennial Report Submissions

International Assessment and Review

Reviews

Preparation of NCs and BRs

Review Reports of National Communications and Biennial Reports

Reports on in-depth reviews of national communications of Annex I Parties

Reports of technical reviews of first biennial reports of developed country Parties

Reports of technical reviews of second biennial reports of developed country Parties

Review Reports of National Communications and Biennial Reports

Multilateral Assessment

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 41

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 42

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 43

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 45

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 46

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 47

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 49

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 50

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 51

Multilateral Assessment at SBI 52-55

Multilateral Assessment at Climate Dialogues 2020

Multilateral Assessment during May-June 2021Climate Change Conference

Austria MA

Belgium MA

Bulgaria MA

Cyprus MA

European Union MA

Finland MA

Greece MA

Kazakhstan MA

Luxembourg MA

Netherlands' MA

New Zealand MA

Portugal MA

Sweden MA

Switzerland MA

Australia MA

Belarus MA

Canada MA

Croatia MA

Czechia MA

Denmark MA

Estonia MA

France MA

Germany MA

Hungary MA

Iceland MA

Ireland MA

Italy MA

Japan MA

Latvia MA

Liechtenstein MA

Lithuania MA

Malta MA

Monaco MA

Norway MA

Poland MA

Romania MA

Russian Federation MA

Slovakia MA

Slovenia MA

Spain MA

Ukraine MA

United Kingdom MA

United States of America MA

First multilateral assessment (MA) working group session of the fifth cycle of the international assessment and review (IAR)

Second multilateral assessment (MA) working group session of the fifth cycle of the international assessment and review (IAR)

Third multilateral assessment (MA) working group session of the fifth cycle of the international assessment and review (IAR)

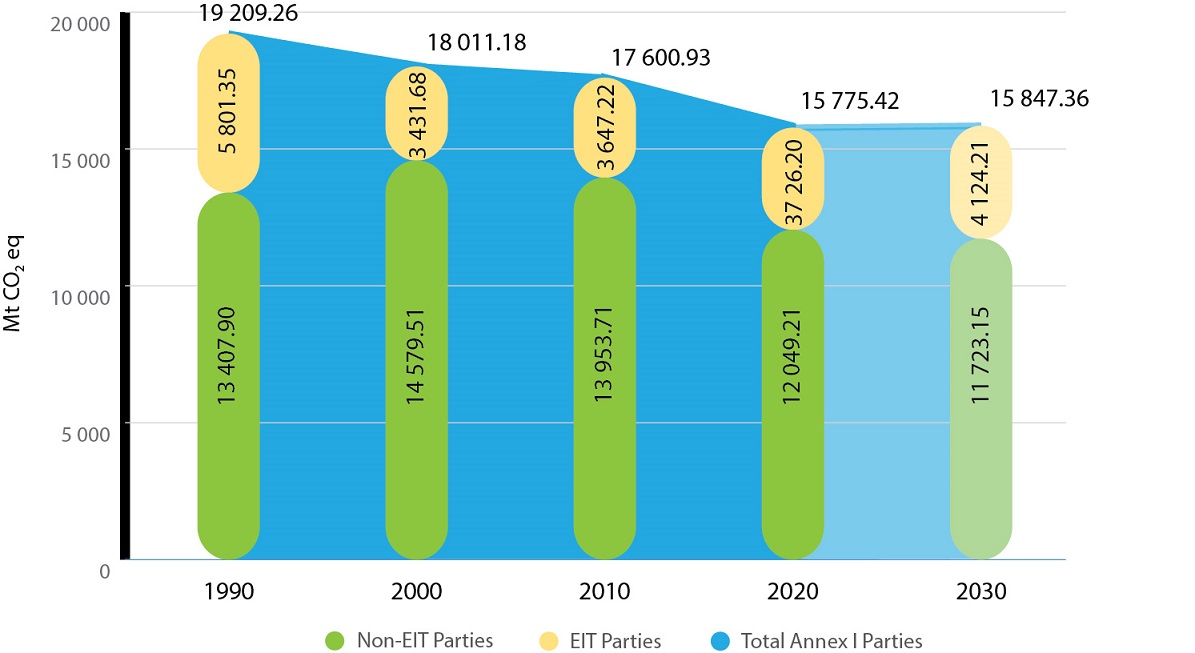

Compilation and Synthesis Reports

https://unfccc.int/MA#How-does-MA-work

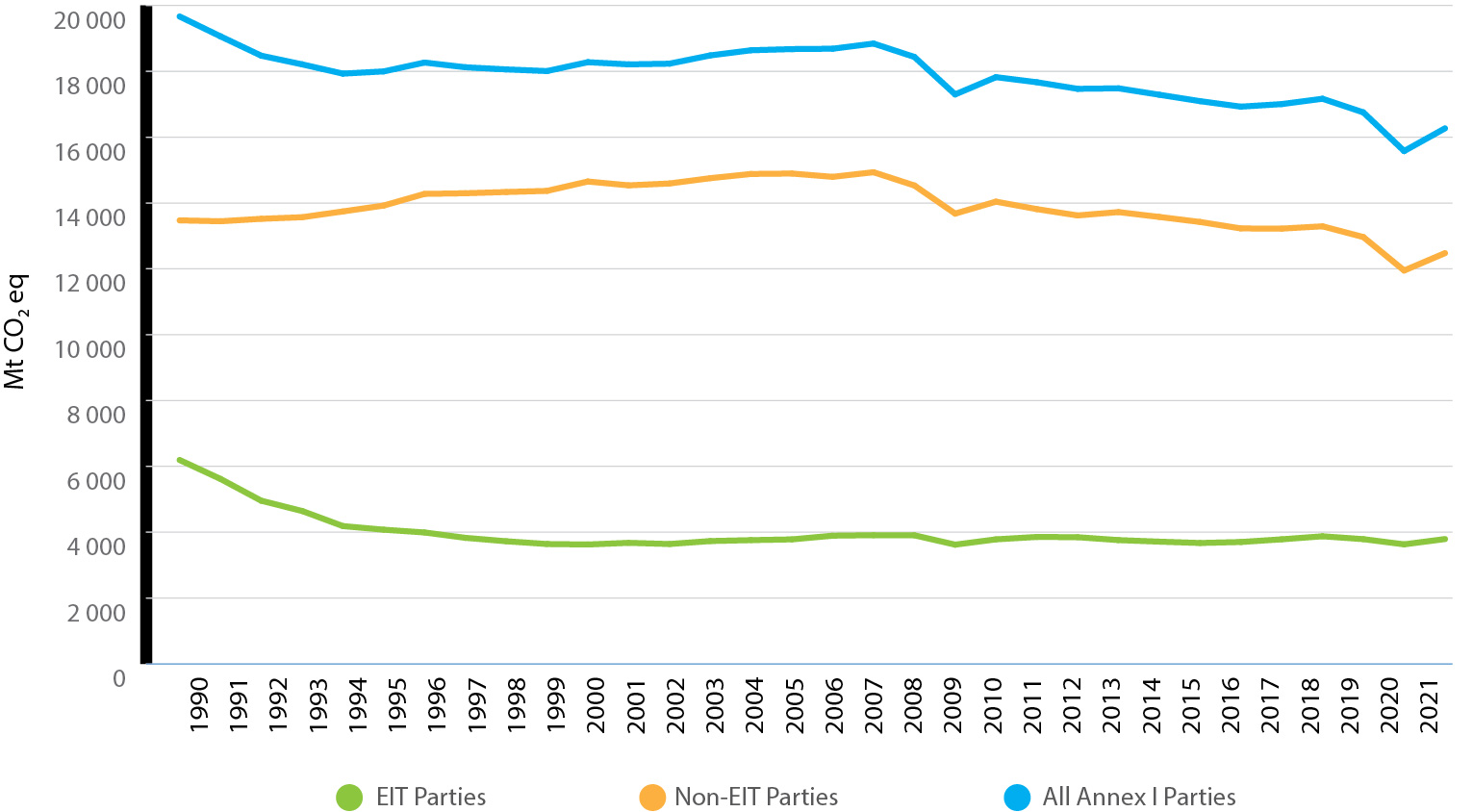

Greenhouse Gas Inventories - Annex I Parties

Reporting and review under the Kyoto Protocol

Transparency data and tools

Methods for climate change transparency

Lead Reviewers Hub

Training programmes for expert reviewers

Support for developing countries

Together4Transparency

Transparency calendar