Bonn, May 19 2016 - The measurable impacts of climate change hold great potential to affect the people who live on this planet. From drought to fire to rising seas to extreme weather events, physical climate impacts also hit entire communities. Recent news on mass human movements has put this trend sharply into focus but measuring and assessing the impact and the individual motivations behind migration accurately and in a balanced way remains critical to any long-term successful response.

But data on the problem has made leaps and bounds and this was what presented during the latest UN Climate Change Conference in Bonn by a group of experts on human migration presented key findings about the link between climate change and migration. At the event “Human Mobility and the Paris Agreement: What’s Next?”, speakers from the University of Liège, the International Organization for Migration, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and the UN University highlighted the importance of reliable data, able to measure climate migration.

With adaptation to climate change recognized as a crucial part of climate action in last year’s Paris Agreement, minimizing these human impacts presents a challenge to governments acting to fulfill their contributions to the agreement.

Various and diverse forms of migration make it difficult to determine exactly why people move. Some displacement is forced, others choose to migrate. Some movement can be directly linked to climate impacts but it is not always clear what role climate plays, if any. Droughts, floods and hazardous weather events often displace people and are sometimes caused or exacerbated by climate change. Slow onset climate impacts such as sea level rise and drought can force people from their homes over time. Secondary effects from climate change, such as conflict or resource scarcity, are not so easy to define yet can trigger mass migration.

For many families, migration can be a conscious choice to adapt to climate change simply by moving to another place to avoid impacts and the panel pointed out that natural resources, food security, drinking water and energy supply are likely to become even more scarce in the future, forcing even more people into difficult choices. The panel stressed that this is not just an issue for the developing world, and that displacement happens everywhere.

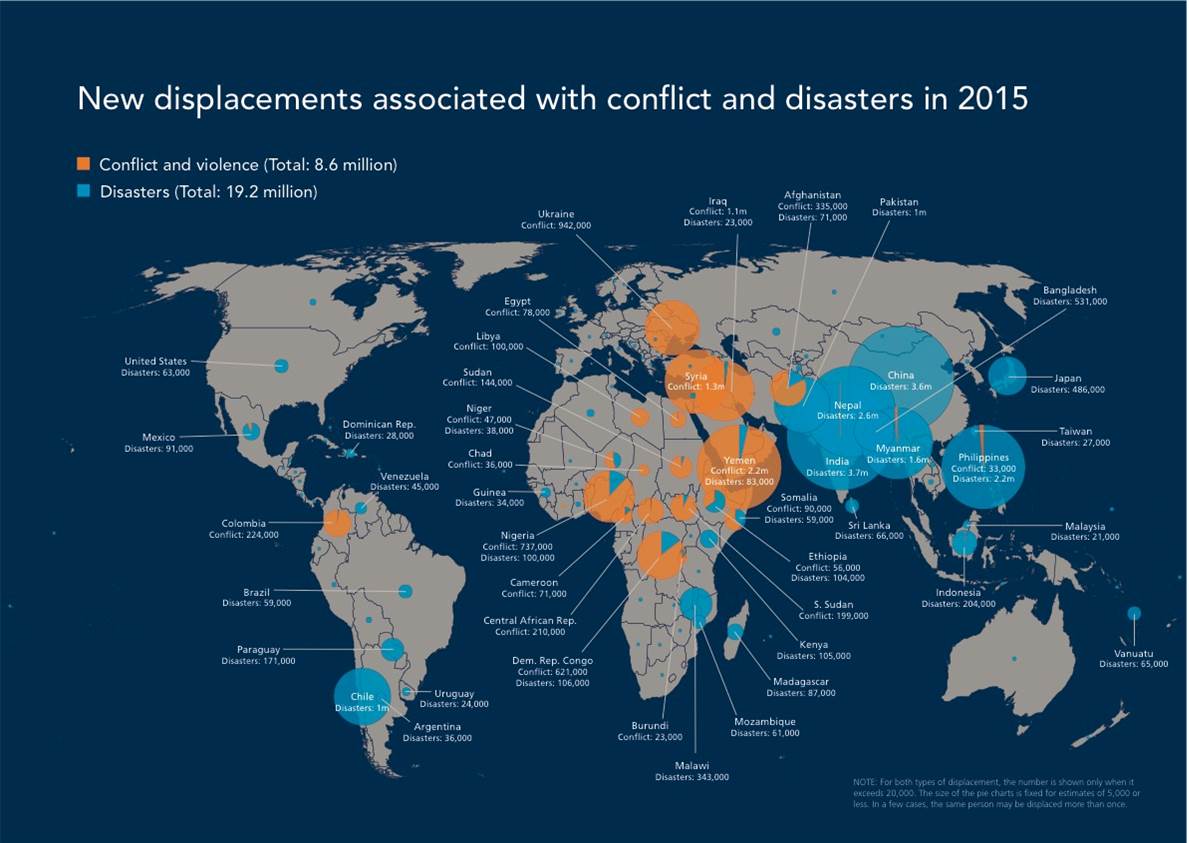

(Graphic - internal displacement monitoring centre iDMC and Norwegian Refugee Council)

A large number of datasets, combined with qualitative interview techniques, makes it easier now to identify climate-related relocation. As multiplier effects, the experts named:

- Frequency and intensity of extreme weather events

- Scarcity of water

- Productive land for livelihoods

- Food security

- Habitability of cost areas

- Potential for conflicts linked to competition over scarce resources

According to the specialists, in 2015, relocations were particularly triggered by floods (56%) or storms (43%), or associated with conflict and disasters (Africa, Middle East) or natural disasters (India). However, droughts and other gradual or recurring slow environmental disasters were not integrated in the databases, since the data is too anecdotal to be aggregated.

(Graphic - internal displacement monitoring centre iDMC and Norwegian Refugee Council)

Composing an Index for Climate Vulnerability

One interesting aspect of migration and climate change was put forth by Robert Oakes from the UN University. He outlined a household survey performed in the Pacific region, on the island nations of Tuvalu, Nauru and Kiribati. On these islands, environmental hazards already impacting people – 95% of surveyed households have experienced disasters such as cyclone, floods, sea level rise, saltwater intrusion, drought or irregular rains. This is already triggering migration, either to other islands or inland, if such an option exists.

However, some people identify as “trapped populations”, or populations who responded that they would have migrated at some point in the last 10 years if they had the means to do so. Half of people who responded that they did not move on Nauru and Kiribati fall into this group. Many cited the lack of financial resources, visas or contacts outside of their area as reasons they are trapped. These are some of the most vulnerable people, and their situation has helped UNU develop a vulnerability index composed of six factors:

- Economic

- Education

- Health and nutrition

- Housing and environment

- Social capital

- Social inclusion

By understanding the relationship between vulnerability and migration in the context of climate change, the global community can put in place policy that helps reduce vulnerability and increase the adaptive capacity of potential migrant populations. Of important note is that the Paris Agreement establishes a task force to develop recommendations for integrated approaches to avert, minimize and address displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change.

Our current refugee crisis shows that instability can come from an increasing displacement of people worldwide. Scientists have determined a clear link between environmental and climate changes, migration and vulnerability. Moving forward, building datasets that strengthen the connection between migration and climate impacts can help governments shape adaptation policy that protects the most vulnerable and improves the prospects of global stability.

This final graphic from the internal displacement monitoring centre - iDMC - shows the scale of last year's overall human movement. Their full report can be accessed here.

(Graphic - internal displacement monitoring centre iDMC)

Pic by Peter Haden (Flickr)