Understanding the UN climate change regime

The 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (referred to as the UNFCCC or the Convention) provides the foundation for multilateral action to combat climate change and its impacts on humanity and ecosystems. The 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2015 Paris Agreement were negotiated under the UNFCCC and built on the Convention.

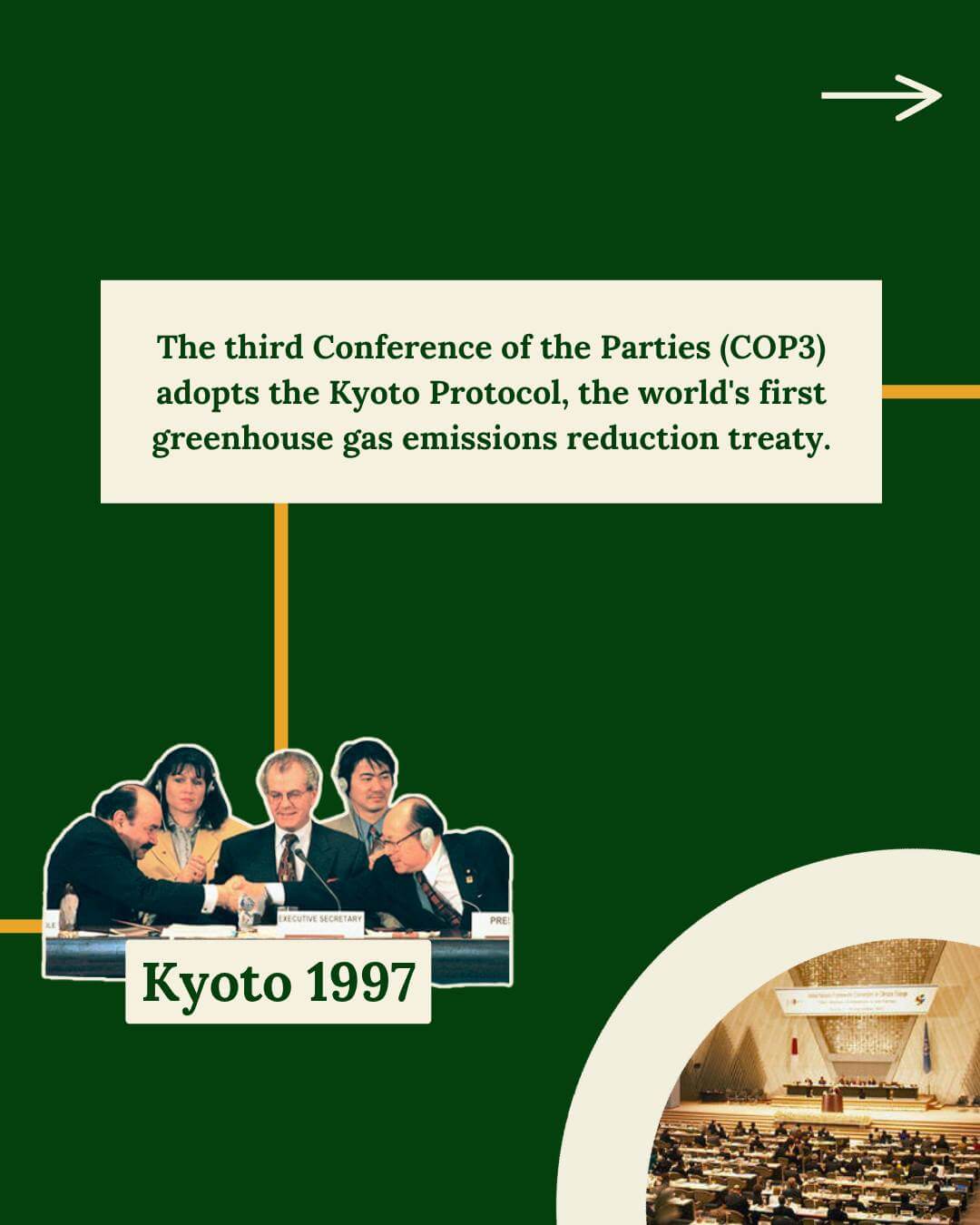

The objective of the UNFCCC is to “stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”. In pursuit of this objective, the UNFCCC establishes a framework with broad principles, general obligations, basic institutional arrangements, and an intergovernmental process for agreeing to specific actions over time, including through collective decisions by the Conference of the Parties, and as well as other international legal instruments with more specific obligations – such as the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement. Governments have also negotiated a protocol to the Convention. The Kyoto Protocol was agreed in December 1997 in Kyoto, Japan. It includes an obligation and individual legally binding emission reduction targets for developed countries. The Protocol had two commitment periods: the first ran from 2008–2012, and the second ran from 2013–2020. There are no further commitment periods under the Kyoto Protocol.

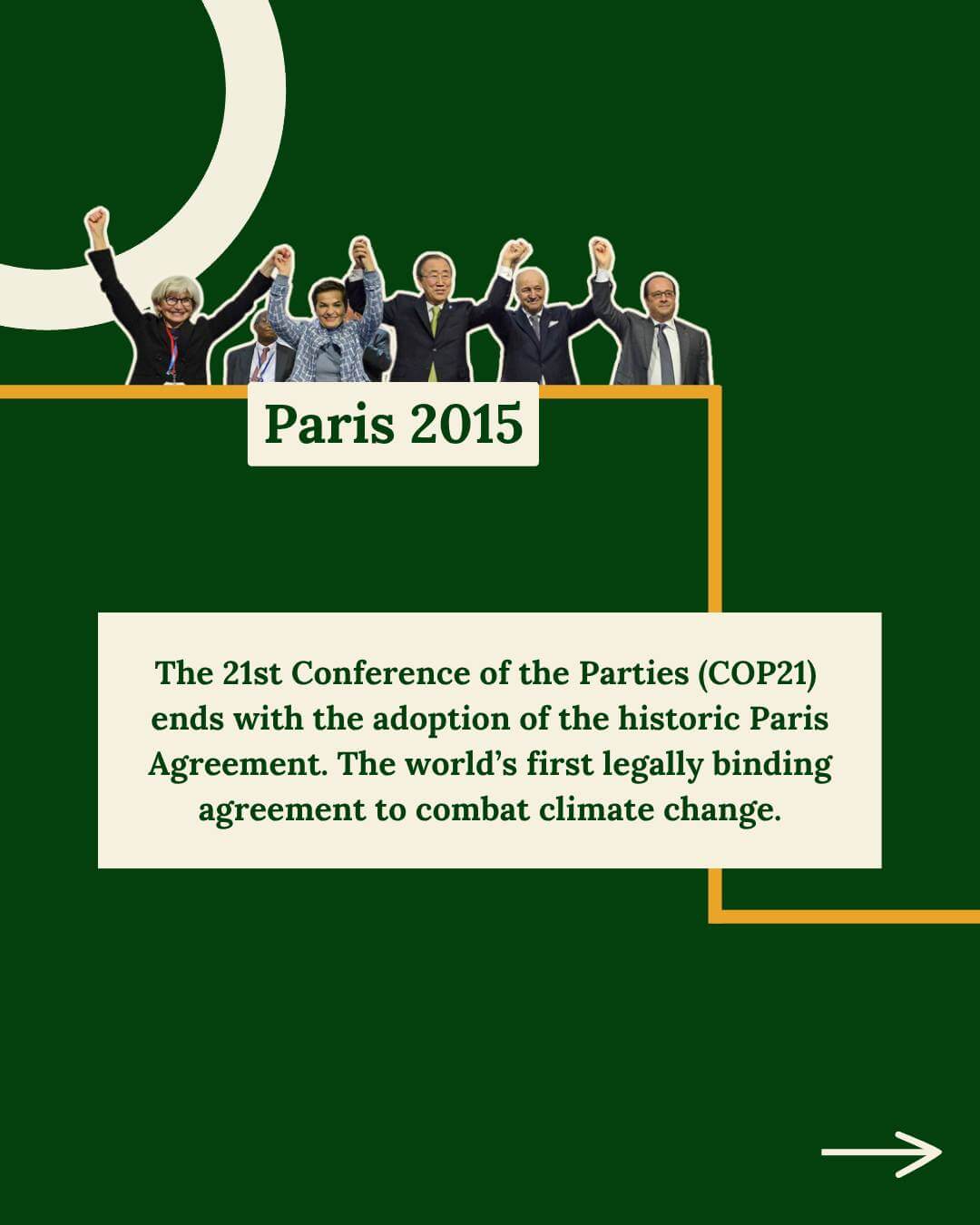

Ten years later, on 12 December 2015, governments adopted the Paris Agreement, which entered into force on 4 November 2016. Its overarching goal is to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” The Paris Agreement is a landmark in the multilateral climate change process because, for the first time, a binding agreement brings all nations together to combat climate change and adapt to its effects.

SCIENCE

Science provides the foundation for understanding climate change and informing policy under the UNFCCC. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assesses global research and issues comprehensive assessment reports, special reports, and methodologies for greenhouse gas inventories. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) publishes annual “State of the Global Climate” reports, providing authoritative updates on trends and impacts.

The Convention encourages research, systematic observation, and cooperation with international programmes. The Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) facilitates dialogue between scientists and policymakers through annual research discussions. Periodic reviews of the long-term global goal, such as the 2013–2015 structured expert dialogue, have informed Parties’ decisions, contributing, for example, to recognition of the 1.5 °C target in Paris.

Science supports every aspect of the regime: setting targets, guiding adaptation, improving transparency, and enabling informed negotiation. It offers consensus-based, policy-relevant but non-prescriptive information. As understanding deepens, the science-policy interface ensures that decisions reflect current knowledge while communicating uncertainties clearly.

Science: why is there a need to act?

The international climate regime is built upon a clear understanding of the threats posed by, and the causes of climate change. More than a century and a half of industrialization, along with the clear-felling of forests and certain farming methods, has led to increased quantities of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere. There are some basic well-established scientific links:

The concentration of GHGs in the earth’s atmosphere is directly linked to the average global temperature on Earth;

The concentration has been rising steadily, and mean global temperatures along with it, since the time of the Industrial Revolution as a result from human activity, primarily the burning of fossil fuels and changes in land use;

As a consequence, there is need to take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and enhance sinks, and to adapt to the impacts from climate change.

This knowledge and understanding of climate change, its causes and effects, has been constantly growing in breadth and depth over the last decades. It is based on the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as well as on research findings of many other organizations. The IPCC has a well-established role as the leading international body for the assessment of climate change. It reviews worldwide research, issues regular assessment reports and compiles special reports and technical papers. The findings of the IPCC reflect global scientific consensus and are apolitical in character. Its assessment reports reflect the work and observations of thousands of scientists from around the world.

The recent years provided more clarity about human-generated (anthropogenic) climate change than ever before. The IPCC released its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), with three Working Group (WG) reports (2021–2022) and a Synthesis Report (2023). The WG I contribution assesses the physical science of climate change and is categorical in its conclusion: climate change is real, and human activities are the main cause.

On average during 2011–2020, the planet was about 1.09 °C warmer than in 1850–1900. The ocean has absorbed most of this extra heat, snow and ice have declined, and global sea level has risen by roughly 20 centimeters since 1901, with the rise accelerating in recent decades. Arctic sea ice has decreased significantly.

What happens next depends on how quickly the world reduces greenhouse gas emissions. By 2100, compared with 1850–1900, a very low-emissions pathway would lead to around 1.4 °C of warming, an intermediate pathway to around 2.7 °C, and a very high-emissions pathway to around 4.4 °C.

Sea level will continue to rise in all cases because oceans and ice sheets respond slowly to temperature changes. By 2100, this rise is projected to be roughly 30 to 60 centimeters in a very low-emissions world and around 60 centimeters to about one meter in a very high-emissions world. Even with strong emission reductions, some changes such as deep-ocean warming, melting ice sheets and sea-level rise will continue for centuries to millennia.

AR6 also provides new estimates of how much carbon dioxide humanity has emitted and how much more can be released if we want to limit future warming. Cumulative human-caused CO₂ emissions from 1850 to 2019 are about 2,390 gigatons. Starting from 2020, the remaining CO₂ budget for a 50 percent chance of limiting warming to 1.5 °C is about 500 gigatons, and this budget is reduced each year emissions continue. Pathways that keep warming close to 1.5 °C reach global net-zero CO₂ in the early 2050s, while those that limit warming to around 2 °C reach net-zero in the early 2070s.

Alongside this physical science assessment from Working Group I, Working Group II analyses impacts, risks and ways to adapt, and Working Group III examines how emissions can be reduced across sectors such as energy, transport, industry, land use and cities.

Together, the reports from the three working groups conclude that deep, rapid and sustained cuts across all areas of human activity are needed this decade and beyond to limit global warming and reduce the growing risks already being observed.

Science: The State of the Climate

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) issues a statement on the state of the global climate every year. It is based on multiple international datasets maintained independently by global climate analysis centers and information submitted by WMO Members’ National Meteorological and Hydrological Services and Research Institutes and is an authoritative source of reference.

What does the UN climate change regime do?

Climate change is inherently global in nature. The emissions of long-lived GHGs into the atmosphere from sources anywhere on the globe will affect atmospheric concentrations. As the dynamics of the climate system are globally integrated, the potential impacts of climate change can affect all parts of the globe. Human emissions of GHGs occur primarily from the production and use of energy by businesses, governments, and individuals, and from land use, these are all activities that are essential for modern life and for raising the standard of living for people everywhere. The composition of the world’s atmosphere is impacted by GHG emissions for countries around the world, and the effects of those changes affect everyone. Hence, there is motivation and need for collective, global action under the UNFCCC – global action that calls for decision making at many levels: international – through intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) and process – regional, national, sub-national, and local – including by local governments, individuals, communities, multinational firms and local enterprises.

Under the UN climate change regime, governments:

Consider latest scientific information and agree on actions to be taken – collectively and/or individually – e.g. launch national strategies and measures for reducing GHGs and adapting to the expected adverse impacts of climate change, or both;

Gather and share information on GHG emissions, national policies and best practices, and develop international guidance (e.g., modalities, guidelines, methodologies);

Cooperate, including by mobilizing and providing finance, technology and capacity-building to developing countries, in support of the planning and implementing of mitigation measures (actions to reduce the emission of GHGs into the atmosphere) as well as adaptation measures (actions needed to respond, increase resilience and reduce vulnerability to the impacts of climate change).

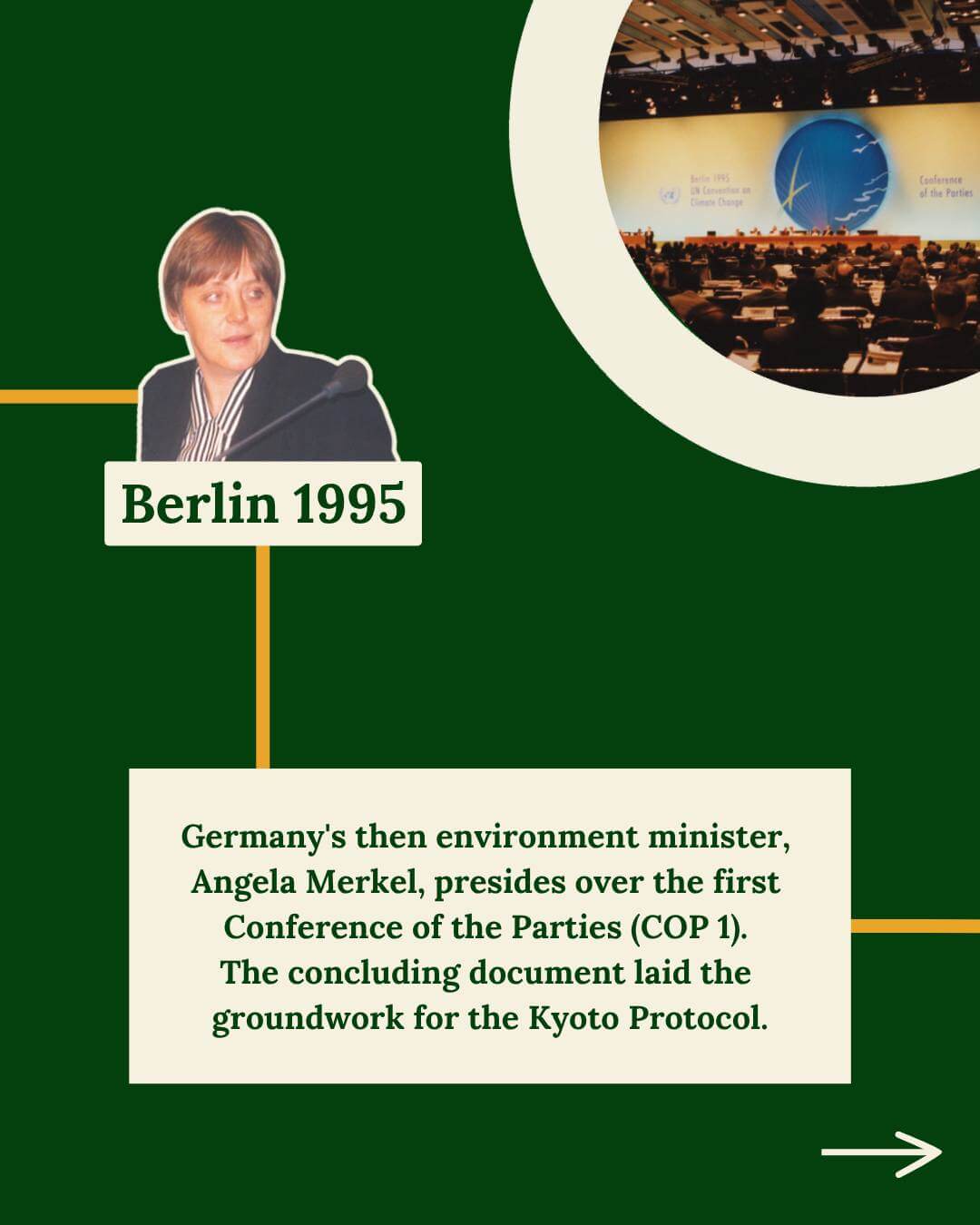

The governments that have ratified the UNFCCC, known as Parties to the Convention, have met annually (except in 2020, when the meeting was postponed for a year due to COVID) as the Conference of the Parties (the COP) since 1995 to take stock of their progress, monitor the implementation of their obligations and continue talks on how best to tackle climate change. Currently, there are 198 Parties to the Convention. Since the Kyoto Protocol’s entry into force in 2005, meetings of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (the CMP) have been held (in conjunction with the annual COP) to review the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol. The Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (the CMA) keeps the implementation of the Agreement under regular review. The Convention established two permanent subsidiary bodies namely the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) and the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), to support the COP. The SBI and the SBSTA also serve the CMP and the CMA. The many decisions taken by the COP, the CMP and the CMA at their annual sessions now make up a ‘rulebook’ (including detailed modalities, procedures and guidelines) for the effective implementation of the Convention, its Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. Through these decisions, the COP, the CMP and the CMA also established a number of institutional arrangements and specialized bodies, often referred to as 'constituted bodies', to support Parties, such as the Adaptation Committee, the and Standing Committee on Finance, the Technology Executive Committee - and many others. An overview of all Convention, Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement bodies can be found here. Thus, a complex architecture for global climate governance has been developed under the Convention and its Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

Under this architecture, Parties agree to further actions as they develop national programmes, plans and measures to mitigate climate change and adapt to its impacts, as well as on support for such actions. The Convention also obliges Parties to share technology, provide financial support and to cooperate in other ways to reduce GHG emissions, especially from energy, transport, industry, agriculture, forestry and waste management, which together produce nearly all GHG emissions attributable to human activities.

The obligations and rules under the UN climate change regime also calls on each Party to report on its national efforts to combat climate change and to develop GHG inventories that list its national sources (such as factories and transport) and its sinks (forests and other natural ecosystems that absorb GHGs from the atmosphere).

THE CONVENTION

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted in 1992 and entering into force in 1994, provides the foundation for coordinated global action to address climate change. Its objective is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations at a level that prevents dangerous human interference with the climate system, allowing ecosystems to adapt naturally, food production to remain secure, and sustainable development to continue. The Convention was visionary for its time, calling for precautionary action even amid scientific uncertainty.

It distinguishes responsibilities between developed and developing countries under the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Industrialized nations listed in Annex I are required to take the lead in reducing emissions because of their historical contributions, while developing countries are encouraged to limit emissions without jeopardizing development, supported by financial and technological assistance. Parties are obliged to prepare national inventories of greenhouse gases and regularly report policies and measures.

Adaptation was recognized as essential but initially received less focus. Over time, growing scientific evidence and increasing impacts elevated its importance. The Convention established financial, technological, and capacity-building mechanisms, catalyzed the creation of bodies such as the Adaptation Committee and Standing Committee on Finance, and laid the groundwork for more detailed agreements, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, which expanded and specified obligations to operationalize its objectives.

A Short History of COPs

THE KYOTO PROTOCOL

Adopted in 1997 and entering into force in 2005, the Kyoto Protocol turned the Convention’s principles into binding commitments for developed countries. It set quantified emission reduction targets for 36 industrialized countries and the European Union, collectively amounting to about 5 percent below 1990 levels during 2008–2012, with a second commitment period (2013–2020) established through the Doha Amendment. The Protocol reaffirmed the principle that those most responsible for emissions must take the lead.

Its design combined legal obligations with flexibility. Through emissions trading, Joint Implementation (JI), and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), it created market-based incentives that allowed countries to meet targets cost-effectively while encouraging low-carbon investment in developing countries. These mechanisms introduced carbon pricing and established global systems for measurement and verification.

Kyoto also pioneered rigorous transparency and compliance provisions: detailed monitoring, standardized reporting, independent expert review, and a Compliance Committee with enforcement and facilitative branches. Though limited to developed countries, and eventually overtaken by the universal Paris framework, it established accounting systems, methodologies, and institutional experience that remain integral to international climate governance.

Photo credit: UN Photo/Frank Leather

THE PARIS AGREEMENT

The 2015 Paris Agreement unified all countries in a shared effort to combat climate change and adapt to its effects. It aims to keep the rise in global average temperature well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C. Unlike Kyoto, it applies to all Parties, requiring each to define and communicate its own nationally determined contribution (NDC) and to update it every five years, representing progression and the highest possible ambition.

Paris introduced a comprehensive framework linking mitigation, adaptation, and support. It set a long-term temperature goal, called for global peaking and balance between emissions and removals in the second half of the century, and recognized forests and other sinks as vital. It also strengthened adaptation through a global goal to enhance resilience and reduce vulnerability, and, in 2023, Parties operationalized new funding arrangements including a Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) with the World Bank as interim host, complementing the Warsaw International Mechanism.

The Agreement’s architecture includes a robust transparency framework for action and support, a mechanism to promote compliance in a facilitative manner, and a global stocktake every five years to assess collective progress. The first global stocktake concluded in 2023 at COP28/CMA5 (the “UAE Consensus”), calling on Parties to transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems and to work towards tripling global renewable energy capacity and doubling the rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030. Developed countries reaffirmed their obligations to provide finance, technology, and capacity-building, while developing countries were encouraged to act according to their capabilities. The Agreement’s five-year cycle of pledges, review, and enhancement is designed to continually raise global ambition.

Photo credit: UN Climate Change/Hajü Staudt

Photo credit: UN Climate Change/James Dowson

Loss and damage

Addressing Climate Impacts Beyond Adaptation

Loss and damage covers impacts that cannot be avoided through mitigation or adaptation. At COP27 and COP28, Parties established and operationalized the Loss and Damage Fund, with the World Bank as interim host. The Fund supports vulnerable countries facing devastating climate impacts, with a governing board and initial pledges now in place. The Santiago Network complements this by providing technical assistance.

Creative commons license / World Vision

Creative Commons license / IFRC-DRK

MITIGATION

Mitigation means human actions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or enhance sinks. It is the key to stabilizing the climate. The UNFCCC requires Parties to pursue mitigation programmes across all major sectors, energy, transport, industry, agriculture, forestry, and waste, through policies, incentives, and technology deployment that make activities cleaner and more efficient. Examples include renewable energy, improved efficiency, and reforestation.

Under Kyoto, developed countries adopted binding emission caps while developing countries pursued specific programmes and projects, including through Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) supported by finance and technology. The Clean Development Mechanism enabled certified reductions from developing-country projects to count toward developed-country targets. Cooperative initiatives also addressed deforestation through REDD-plus, focusing on reducing emissions, conserving forest carbon stocks, and sustainable management of forests.

Market mechanisms are central to mitigation. Kyoto’s instruments, emissions trading, JI, and CDM, showed how economics can drive emission reductions efficiently. Under the Paris Agreement’s Article 6, Parties agreed detailed guidance for cooperative approaches (Glasgow, 2021) and advanced operationalization of the Article 6.4 mechanism, adopting core standards in 2024 and establishing registry connectivity at COP29 (2024), with credit issuance to begin as the mechanism becomes operational. Together with national policies and investments, these mechanisms support the transition toward low-emission pathways.

What is the UN Carbon Market?

ADAPTATION

Adaptation involves adjusting natural and human systems in response to climate impacts, moderating harm and seizing opportunities. It includes structural and policy measures, from flood defences and drought-resistant crops to social protection and planning reforms. Because climate risks differ by region, adaptation must be context-specific, integrating scientific, local, and indigenous knowledge.

Under the Convention, Parties began addressing adaptation systematically in 2001 through the Marrakesh Accords, which established the Least Developed Countries Fund and Expert Group (LEG) and launched National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs). Later frameworks, such as the Cancun Adaptation Framework (2010) and the Adaptation Committee, increased coherence. The Nairobi Work Programme enhances information exchange and good practices.

The Paris Agreement elevated adaptation by setting a global goal to enhance adaptive capacity, strengthen resilience, and reduce vulnerability; in 2023, Parties adopted the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience under the Global Goal on Adaptation and launched a two-year UAE–Belém work programme to develop indicators to track progress.

CLIMATE FINANCE

Climate finance is the provision and mobilization of funds from public, private, and alternative sources to support mitigation and adaptation, particularly in developing countries. The Convention, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement recognize that those with greater financial capacity and historical responsibility must assist others. Financial resources are essential for clean energy transitions, resilient infrastructure, and risk reduction measures.

The Convention established a Financial Mechanism, served by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and, later, the Green Climate Fund (GCF), to channel resources to developing countries. Two special funds, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), also operate under the GEF, while the Adaptation Fund, created under Kyoto, finances concrete projects and programmes. The Standing Committee on Finance (SCF), created in 2010, enhances coordination, prepares biennial assessments of finance flows, and convenes forums to strengthen coherence.

OECD data indicate the USD 100 billion goal was reached in 2022; at COP29 (2024), Parties agreed a new collective quantified goal to triple finance to developing countries to USD 300 billion per year by 2035, alongside a broader mobilization goal of USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035 from all sources. The Paris Agreement reaffirms developed countries’ obligations and calls for finance flows to align with low-emission, climate-resilient pathways. Transparency and predictability are strengthened through reporting under the Enhanced Transparency Framework and the UNFCCC finance portal, ensuring clarity on both support provided, and support needed.

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER

Technology development and transfer are crucial to reduce emissions and enhance resilience. The Convention commits all Parties to promote cooperation in developing and transferring environmentally sound technologies, while developed countries must take practical steps to finance and facilitate access for developing countries. This encompasses both mitigation tools, such as renewable energy and efficiency technologies, and adaptation technologies, including early warning systems and resilient infrastructure.

In 2010, Parties established the Technology Mechanism, comprising the Technology Executive Committee (TEC) and the Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN). The TEC provides policy guidance and analysis, while the CTCN offers technical assistance, builds capacity, and fosters partnerships through National Designated Entities. This dual structure links policy and implementation.

The Paris Agreement further strengthened this framework by creating a technology framework to guide the Mechanism’s work, enhance synergy across the innovation cycle, and connect technology support to the transparency and stocktake processes. Earlier initiatives such as the technology transfer framework (2001) and the Poznan Strategic Program supported pilot projects and capacity-building. TT:CLEAR serves as the UNFCCC’s information hub for technology cooperation, enabling countries to share knowledge and track progress.

CAPACITY-BUILDING

Capacity-building helps individuals, institutions, and systems acquire the knowledge, skills, and resources needed for effective climate action. It spans education, training, institutional strengthening, and enabling environments for policy, finance, and technology. The Convention emphasizes that capacity-building should be country-driven, participatory, and responsive to national circumstances.

Frameworks adopted in 2001 guide this work, focusing on developing countries and economies in transition. They outline principles such as learning by doing and building on existing activities, and they highlight priority areas including technology transfer, adaptation, and education. The Durban Forum provides a platform for stakeholders to share experiences, while the Paris Committee on Capacity-building (PCCB) coordinates coherence across the system. The Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency (CBIT), supported by the GEF, strengthens institutional and technical capacity for reporting.

The Paris Agreement’s Article 12 broadens capacity-building through “Action for Climate Empowerment” (ACE), encompassing education, training, public awareness, and participation. The Glasgow work programme on ACE (2021–2031) and a four-year ACE Action Plan adopted at COP27/CMA4 (2022) now guide implementation, including annual ACE Dialogues. Together, these arrangements build human and institutional capabilities that sustain long-term climate action.

NDCs

Before Paris, countries submitted Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) outlining their planned actions. Once the Paris Agreement entered into force, these became each Party’s first Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), unless revised. NDCs are at the core of the Paris architecture, representing each country’s commitment to mitigation, and, where relevant, adaptation and support.

The Agreement requires all Parties to prepare, communicate, and maintain successive NDCs, to pursue domestic measures to achieve them, and to increase ambition over time; following the first global stocktake, Parties are requested to submit their next NDCs in 2025 including with 2035 targets. Parties provide information for clarity, such as targets, baselines, assumptions, sectors, and metrics, and submit NDCs to a public registry maintained by the secretariat. Developed countries are expected to maintain absolute economy-wide targets, while developing countries progressively move toward them.

Long-term low-emission development strategies complement NDCs by charting pathways consistent with the Agreement’s temperature goals. NDCs and long-term strategies feed into the five-year Global Stocktake, which assesses collective progress and guides the next cycle of contributions. This iterative approach makes the Paris Agreement dynamic, flexible, and continuously improving.

Photo credit: UN Climate Change/Kiara Worth

What are the NDCs and why are they important?

TRANSPARENCY

Transparency and accountability are cornerstones of the regime. The Convention established reporting obligations for all Parties, requiring national communications and greenhouse gas inventories. Annex I Parties also submit Biennial Reports detailing mitigation progress and support provided, while non-Annex I Parties submit Biennial Update Reports with flexibility for capacity. These reports are reviewed by expert teams and considered multilaterally.

The Kyoto Protocol added legally binding reporting and a compliance system, including expert review teams and the Compliance Committee, to verify adherence to commitments. The Cancun and Durban decisions strengthened measurement, reporting, and verification through the International Assessment and Review (IAR) process for developed countries and International Consultation and Analysis (ICA) for developing countries.

The Paris Agreement replaced earlier systems with an Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) for all Parties, requiring Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) at least every two years; the first BTRs were due by 31 December 2024 and submissions began in late 2024 and 2025. Reports undergo technical expert review and facilitative consideration of progress. The ETF underpins the Global Stocktake, ensuring clarity, comparability, and trust in collective action.

5 reasons why transparency is essential for climate action

NEGOTIATIONS

UN climate change negotiations are the process through which Parties review progress and adopt new decisions to strengthen implementation. The Conferences of the Parties (COP), together with the CMP (Kyoto) and CMA (Paris), are the supreme decision-making bodies, supported by subsidiary bodies (SBI and SBSTA) and various constituted bodies.

Sessions typically run for two weeks, with the first week focusing on technical work and the second on ministerial discussions and high-level decisions. Agendas cover mitigation, adaptation, finance, technology, capacity-building, transparency, and procedural matters. Most negotiations proceed by consensus, with smaller contact groups and informal consultations refining texts before plenary adoption.

Observers, including civil society, youth, indigenous peoples, and the private sector, participate widely, making COPs some of the largest UN gatherings. Between sessions, bodies established by the COP continue substantive work, ensuring implementation and continuity. Over time, the negotiation process has evolved from rulemaking toward continuous improvement, transparency, and coordination across the global climate regime.