Coral reefs are one of the true wonders of the world, remarkable ecosystems in their own right; living, breathing animals that are an incredibly important part of our natural world. Some 4,000 species of fish and around 25 per cent of marine life rely on coral reefs at some point in their lives. They also help form other ecosystems. Right now, coral reefs cover more than 284,000 sq km, mostly in the warmer equatorial waters of the Red Sea, The Indian Ocean and the Pacific. Also, as David Obura, IUCN Coral Specialist Group, points out, local communities rely on coral reefs for their livelihoods. “They provide many ecosystem services to people, including food, coastal protection, medicines, safe passage and harbours, and recreation,” he says. “Most countries with coral reefs are low income countries, and ecosystem services are disproportionately important to their coastal communities, so reefs provide essential foundations for human welfare and national economies, says Obura, who is also a member of the Earth Commission and CORDIO East Africa.” The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates the net economic value of the world’s coral reefs to be tens of billions of US dollars per year, by contributing to tourism and fishing and marine industries.

Scientists first started noticing something was wrong in the 1980s, when the first coral bleaching events were recorded, according to Dr Helen Fox, Conservation Science Director at Coral Reef Alliance. “In 1994, a group of divers noticed that human impacts were having a real effect on the health of coral reefs, and they wanted to do something about it – and that’s where we come in. They got together and formed the Coral Reef Alliance (CORAL), and we immediately got to work galvanising the SCUBA community around reducing human impacts on reefs.”

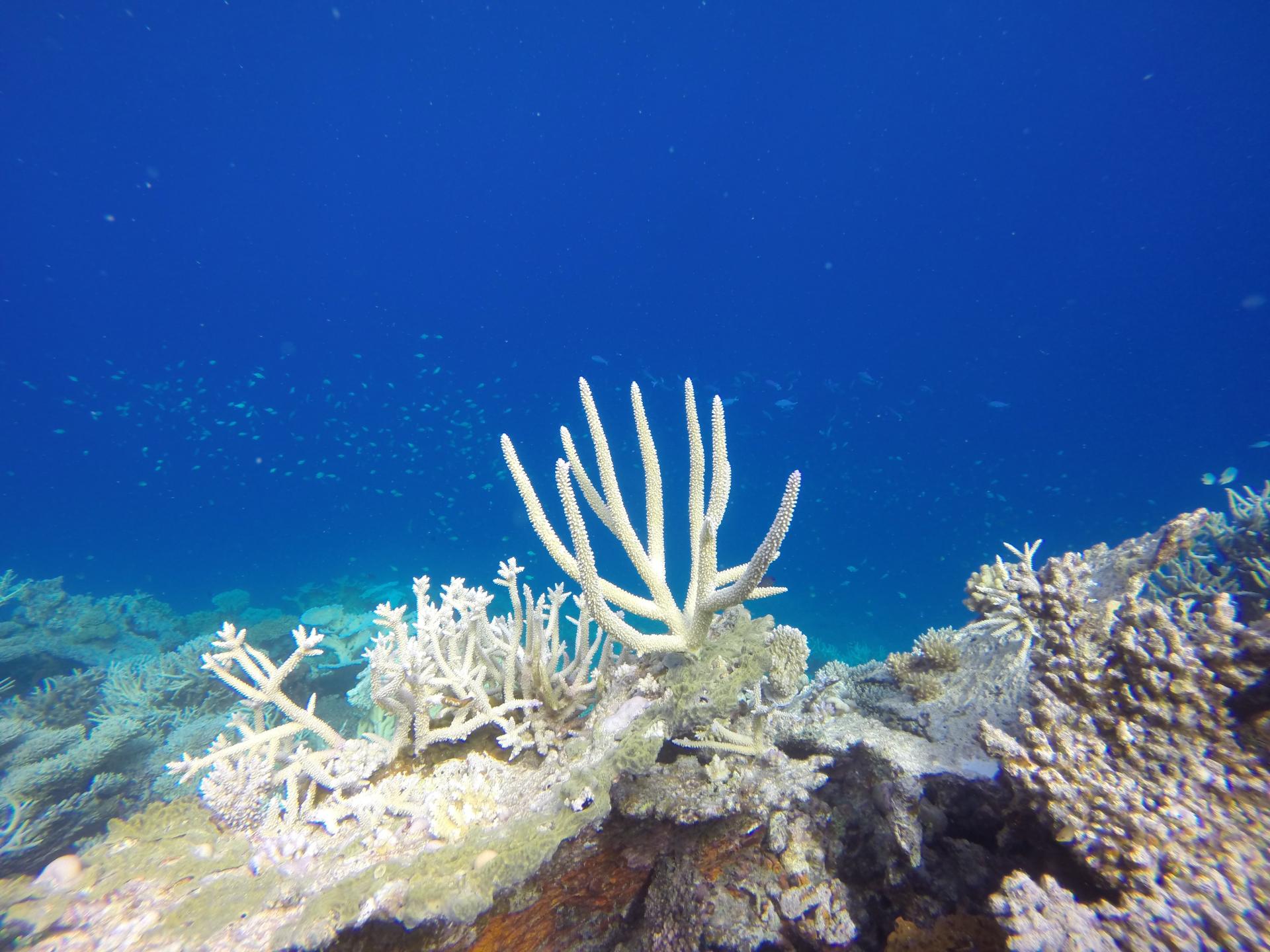

Healthy corals depend on microscopic algae that live in their tissues and are the coral’s main food source, and give coral their colour. When bleaching occurs – usually due to increased sea temperatures – the algae leave the coral, leaving it white or pale and more susceptible to disease. Between 2014 and 2017, an unprecedented bleaching took place, which effected more than 75 per cent of the world’s tropical reefs. “Corals have a very specific temperature range in which they thrive,” says Dr Fox. “If oceans get too warm, it can cause them to bleach, and if the bleaching goes on for too long they can ultimately die. Our research shows that corals can survive some long-term increases in temperatures if they’re healthy, because they have a strong evolutionary response and they can adapt to these changes. But if we don’t curb our carbon emissions quickly and slow down the rate of climate change, corals won’t be able to keep up.”

Reefs also have a role to play when it comes to reducing emissions. While reefs are not a net absorber of CO2, they have a vital role to play. “[Coral reefs] are closely associated with seagrass beds and mangrove forests, which are major carbon sinks, and many deep lagoons and shelves where carbon may be sequestered through sedimentation,” Oburo says. “Losing coral reefs may not only undermine these systems, but perhaps liberate stored carbon, such as where seagrasses and mangroves lose the storm protection that coral reefs provide [by buffering the shoreline against storms and waves].”

“Coral reefs are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet,” says Dr Fox. “They are home to 25% of all marine life. And they also provide benefits for over 1 billion people around the world and provide more than $375 billion in services each year. If we don’t take action now, we could lose coral reefs. And that wouldn’t just be a biodiversity crisis, it would also be a humanitarian and an economic crisis.”

So, how close are we to a tipping point where the world’s coral reefs go extinct? Last year, UNEP published a report that outlined two possible scenarios: a worst-case scenario, where every coral reef in the world will bleach by 2100, with annual severe bleaching taking place by 2034, nine years ahead of the predictions published four years ago. UNEP’s other scenario – if countries exceed their current pledges to limit carbon emissions by 50 per cent – would see severe bleaching delayed until 2045. A bleached coral is more vulnerable to both disease and starvation and it can take decades for them to recover.

Indeed, UNEP’s latest report on corals, published in at the start of October, revealed the loss of 14 per cent of the world’s coral since 2009. Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), which provided financial, technical and communication support to the report said, “Since 2009 we have lost more coral, worldwide, than all the living coral in Australia. We are running out of time: we can reverse losses, but we have to act now. At the upcoming climate conference in Glasgow and biodiversity conference in Kunming, decision-makers have an opportunity to show leadership and save our reefs, but only if they are willing to take bold steps. We must not leave future generations to inherit a world without coral.”

Yet, some progress has been made. “We can now map reefs at finer resolutions and to the global scale, we have sensors and satellites that can return information on reefs that was never possible before,” Obura says. “And we are finally breaking into stride to fully recognise the primary importance of communities and people living adjacent to coral reefs and in whose territories those reefs exist as primary custodians with a vested interest in maintaining them in a healthy state. Turning efforts to local levels to assure sustainability of reef uses and actions at these scales, then building up to national and regional levels to meet targets we are setting globally will be critical to make as much progress on coral reef conservation as we have made on science.”

“I am optimistic that we can save some if not all coral reefs, but we do need to act quickly,” says Dr Fox. “The work that’s happening in local communities around the world to address some of the biggest human impacts on coral reefs, like overfishing and wastewater pollution, gives me hope. And I fervently hope that in these coming weeks we’ll see our global leaders make real commitments to curb carbon emissions and slow the rate of climate change. It has to be done – we don’t have any other choice.”